Exercises from "Fundamentals of Astrodynamics" Part 6

28 Mar 2020In this post, we’ll focus on a multi-part problem in chapter 1 of “Fundamentals of Astrodynamics” by Bate, Mueller, and White, that introduces some basics of orbit determination, namely eccentricity.

Exercise 1.8 Identify each of the following trajectories as either circular, elliptical, hyperbolic, or parabolic:

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

Solution:

Our goal to determine the type of orbit for all of the following will be to find an expression of eccentricity, , based on our knowns. However, in some cases it is unnecessary to solve for because often as an intermediate step, it is necessary to find the specific mechanical energy, , which can at the very least inform of us as to whether the orbit is elliptical (circular being a special case) ( < 0), parabolic ( = 0), or hyperbolic ( > 0). Prove this to yourself be examining equations 1.4-2 and 1.6-4 from the book.

a.

Given a scalar position and velocity, and , respectively, we seek to equate these to eccentricity. However, we cannot solve for only knowing these two parameters. But luckily for us, these problems only require declaring what type of orbit it is. As prefaced above, we can do that by solving for specific mechanical energy, :

where is velocity, is position, and is the gravitational parameter (for our purposes equal to unity due to working in canonical units). Solving this yields a positive result:

The orbit is therefore hyperbolic. Let’s take this a step further and attempt to solve for using equation 1.6-4 from the book to prove to ourselves this is the case:

where is specific angular momentum. But what is ? We can’t solve for an exact value for without knowing the flight path angle, , because and are scalars. But that doesn’t matter. We don’t care what is as long as it’s not zero, which would only be the case for a degenerate conic (essentially a point in space or straight line), because is squared in the above equation. The leap in insight here is to see that because one is being added to a positive number greater than zero under the square-root, must be greater than one and therefore the orbit is a hyperbola.

b.

We can solve for using the polar equation of a conic section knowing the semi-latus rectum, , and that the periapsis distance, , occurs when the true anomaly, , is zero as follows:

The resultant eccentricity being unity means the orbit is a parabola.

c.

Given and , we can use equation 1.6-4 from the text with a simple substitution for the specific angular momentum, , and solve directly for :

The resultant eccentricity being zero means the orbit is a circle.

d.

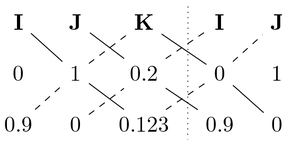

Only being given vectors for position, , and velocity, , we must find both and before we can solve for . The specific angular momentum can easily be solved for using Sarrus’scheme to find the cross-product:

The specific mechanical energy is a function of the scalars velocity and position:

We can now solve for the eccentricity using equation 1.6-4 from the text:

The resultant eccentricity being less than one means the orbit is an ellipse.

e.

This final problem can be solved in the exact same way as the previous. For brevity, I’ll skip any explanation and just show steps:

The resultant eccentricity being greater than one means the orbit is a hyperbola.

eccentricity periapsis apoapsis velocity specific mechanical energy trajectory equation